A (not so) Brief History

At the ripe old age of 10, I wasn’t really reading comics so much as absorbing their essence via a combination of cultural osmosis, cover art, and trading cards. My dad had a plethora of comic books cloistered heavily in the attic of our house and the only way to gain access to them was to ask him specifically to see them. He would often let me during his organization times in the den. I would pour only over the covers themselves.

– Me, probably

Since Fantastic Four was among his favorites, that was one I often looked at. My favorite was, obviously, the dude who was on fire.

Once he began collecting the Marvel Masterworks collections, suddenly comics were in a much more obtainable spot: his den. What once was an obstacle to get to was now right there in full view. Fantastic Four was technically one of the first comics I ever read, and it was from Issue #1. Unfortunately, my 10 year old brain was most certainly not equipped to handle the density of Silver Age Dialogue, so I found myself bored to tears.

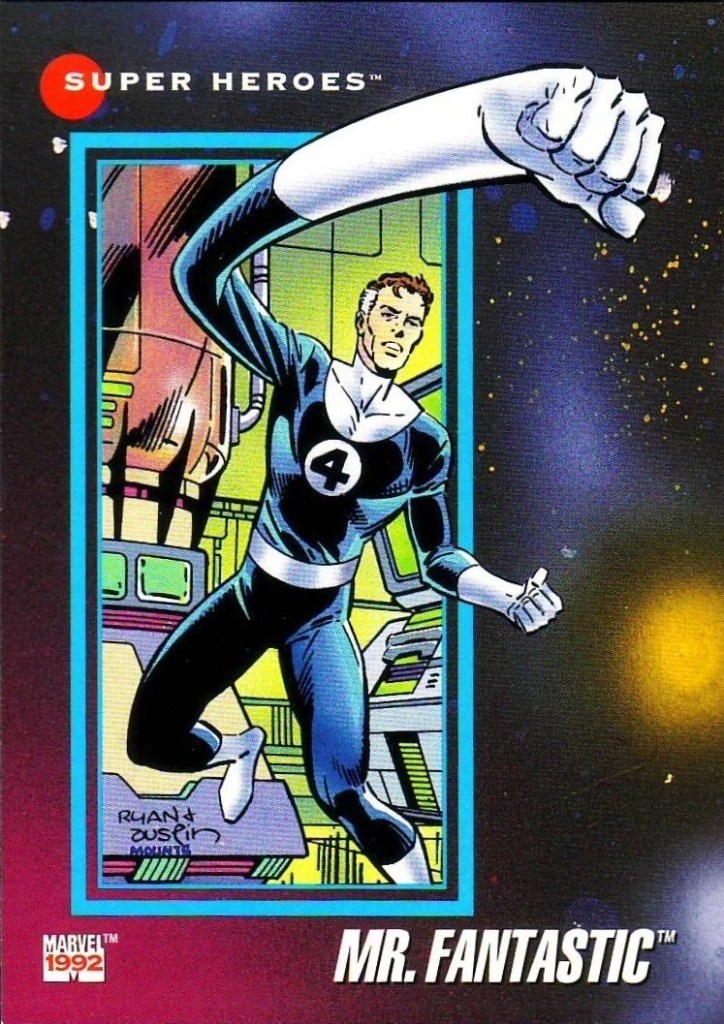

This didn’t stop me from loving the concept of these characters, though. Trading cards were a perfectly serviceable avenue for getting my comic book fix. I’d study the backs of them like they were sacred texts – pretending that knowing a character’s numbered power levels and a boiled-down 1-2 paragraph synopsis of a character equated to comics expertise (it didn’t).

So childhoods were steeped in comic lore, the playground filled with screaming about which Mortal Kombat, Street Fighter, or Marvel characters we were. I’m certain a teacher could have heard me from the classroom screaming “FLAME ONE” once or twice.

Fast forward 7ish years and I was finally ready to take the comic plunge – but it wasn’t Fantastic Four. I wasn’t opposed to reading them or anything but they mostly served as background characters within the greater Marvel world. They were in Secret Wars’, Illuminati side-stories, Civil Wars, or World War Hulk. Sometimes they were crucial to the plot, sometimes they just kind of stood around looking important. But they were never my team – even if I did read a few issues here and there that I had during my big leap into comics.

Then, in 2020, I did something kind of ridiculous: I decided to read almost every X-Men comic ever made. That journey took me years—with lots of breaks and detours—but I made it through. And when that chapter ended, I had to ask myself: “Who’s next?”

The answer came faster than I expected: Marvel’s First Family.

Where to Start?

Instead of starting from the very beginning, like I did with X-Men, I wanted to skip Lee and Kirby. I had read their run in various forms multiple times and I knew I would get lost in so many issues in that Silver Age dialectic that I would eventually be burned out too quickly. I wanted something that felt new for me.

What follows is a breakdown of the major creative eras of the Fantastic Four that I read during this journey – each with its own tone, strengths, quirks, and place in the team’s larger history. Some were instant favorites. Others felt transitional or strange. But each one helped me understand just how varied and enduring Marvel’s First Family really is.

Stan Lee & Jack Kirby

Lee and Kirby weren’t just making comics – they were creating a mythology

Let’s get this out of the way first: I didn’t reread the Lee and Kirby run during this readthrough—but it doesn’t matter. You have to talk about it. You have to mention it. Because this isn’t just the origin of the Fantastic Four—it’s the blueprint. This run was the standard by which all others are measured. It’s not just quintessential FF; it’s foundational Marvel.

It all begins with a rocket launch. Reed Richards, Susan Storm, Johnny Storm, and Ben Grimm take a dangerous trip into space that ends with cosmic rays and the birth of Marvel’s First Family. And from there, it just doesn’t stop. Lee and Kirby were inventing new ideas, characters, and genres in real-time. The team battles the Mole Man. They tangle with Namor. They face off against the Skrulls, the Red Ghost, and the Puppet Master. Doom arrives with theatrical flair. And then the ante just keeps rising—the Negative Zone, the Inhumans, the Silver Surfer, the coming of Galactus. Galactus. This run casually tosses out one of the most influential sci-fi god-figures in all of comics like it’s just another Tuesday.

But it’s not just about big threats and villains. It’s the interpersonal dynamics that make this run endure. The bickering between Johnny and Ben. The deep, simmering affection between Reed and Sue, even as Reed buries himself in work. The way the team acts like a family—fighting, joking, loving—even when they’re fighting aliens. They weren’t just superheroes. They were cosmonauts. Explorers. Intrepid scientists. A dysfunctional but fiercely loyal family hurtling through the weirdest corners of the universe.

And Jack Kirby’s art? It’s phenomenal. There’s a reason his name is on the Mount Rushmore of comic book artists. His designs were wildly imaginative, but his panel layouts were even more impressive. He made science fiction feel real. His cosmic landscapes were dense and electric. Machines buzzed with unnecessary wires and enormous dials, every page vibrating with energy. He didn’t just draw scenes—he conjured worlds. Whole galaxies felt like they existed just beyond the borders of each panel. Every new page felt like opening the hatch of a starship into the unknown.

This run is fun. Like watching a big, loud sci-fi pulp serial on Saturday mornings, but with emotional depth baked in. Reading it today can be a dense experience—Silver Age dialogue is its own beast—but the sheer creativity and ambition is unmatched.

You don’t have to read every issue to get why it matters. You just have to feel it. Lee and Kirby weren’t just making comics – they were creating a mythology. And every Fantastic Four run that came after is still, in some way, orbiting their cosmic legacy.

Roy Thomas & George Perez

This run wasn’t about reinvention, but preservation.

Roy Thomas stepping in after the departure of Lee and Kirby was no small thing. He didn’t try to replicate the explosive inventiveness of his predecessors—instead, he focused on keeping the ship steady during a time of transition. This run wasn’t about reinvention, but preservation. The tone was firmly Bronze Age, which meant more grounded plots, more introspection, and a slower pace that occasionally flirted with forgettability—but also had its own quiet strengths.

George Pérez’s early work on the book was already showing signs of the dynamic, detailed artistry that would make him a legend. Even in these formative years, his panel compositions were crisp, his characters expressive, and his action scenes kinetic. There’s a sense of reliability and momentum to his storytelling—even if the stories themselves weren’t as bold as those in the Lee/Kirby era.

Story-wise, there were some notable beats: Ben Grimm’s continued emotional arc, Sue’s increasing agency in the team, and the tension that always seems to bubble beneath Reed’s stoic surface. It’s also during this period that you start to see the seeds of the more complex familial storytelling that future writers would run with—stories that were less about cosmic threats and more about what it means to be a team.

This era doesn’t always get the spotlight—and maybe that’s fair—but it deserves credit for keeping the FF alive and intact during a period when many fans probably wondered if the magic could ever be recaptured. Thomas and Pérez didn’t dazzle, but they didn’t falter either. They were the calm after the storm—and the foundation for what came next.

Len Wein & George Pérez

Wein added a touch more emotional depth and interpersonal complexity, particularly for characters like Ben and Sue.

Len Wein’s run with George Pérez marked a transitional moment for the Fantastic Four—a quieter pivot between eras that still managed to carry weight. Coming off Roy Thomas’s steadiness, Wein added a touch more emotional depth and interpersonal complexity, particularly for characters like Ben and Sue. There was a growing sense of reflection within the team. The characters weren’t just reacting to cosmic threats—they were reacting to each other, which helped layer the book with more grounded, personal storytelling.

George Pérez’s art, by this point, had begun evolving into something special. You can see the early glimmers of what would make him one of the most celebrated superhero artists of his generation: rich paneling, expressive characters, tight action choreography. His pages weren’t as bombastic as Kirby’s or as sleek as Byrne’s would be, but there was a storytelling clarity that gave the book structure, even when the stories weren’t particularly revolutionary.

This era didn’t introduce world-shattering arcs or redefine what the FF could be—but it did show a team trying to find its place in a post-Kirby world. There’s a bittersweet charm in watching the FF face more grounded challenges while still dipping into the occasional cosmic detour. It felt like a team transitioning, shedding some Silver Age skin and testing new directions.

It might not be anyone’s favorite run, but it deserves credit. Wein brought an editorial polish, a clear affection for the characters, and the kind of connective tissue the book needed to survive—and eventually thrive—through another decade of reinvention.

Doug Moench & Bill Sienkiewicz

The stories weren’t bad—in fact, some were downright intriguing—but they lacked the spark to make them memorable.

Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz’s brief time on Fantastic Four often feels like the forgotten cousin at the cosmic reunion—there, present, polite, but not quite sure where to sit. This was a run that clearly wanted to experiment, but felt boxed in by uncertainty. Editorial didn’t seem to know what they wanted the FF to be in the post-Lee/Kirby world, and it showed in the book’s identity crisis.

Moench, who had done stellar work elsewhere (hello Moon Knight), brought interesting plot seeds to the table—hinting at deeper emotional conflicts and playing with more atmospheric setups. But those ideas never quite had the room to blossom. The stories weren’t bad—in fact, some were downright intriguing—but they lacked the spark to make them memorable.

Sienkiewicz, too, was still finding his voice in superhero comics. The wild, expressionist style that would later redefine visual storytelling in New Mutants and Elektra: Assassin was still cocooned. His work here was much more restrained, sticking to the standard superhero aesthetic. The occasional flashes of flair were exciting, but inconsistent. You can almost feel him pulling his punches.

That said, there’s something fascinating about this run in hindsight. It’s a quiet crossroads for both creators. You can see Sienkiewicz’s potential straining against the page, and Moench trying to bring something moody and personal into a book known for bombast and cosmic chaos.

It’s transitional. It’s weird. And while it may not have reshaped the FF’s legacy, it remains a compelling little echo of what could have been—right before the book took another big leap forward.

Marv Wolfman & Keith Pollard

Wolfman wasn’t trying to revolutionize the FF. He was trying to stabilize them.

Marv Wolfman’s tenure on Fantastic Four is another one of those quiet bridges in the team’s publishing history—easy to overlook, but sturdier than you’d think. Coming in after a string of short and often uncertain creative runs, Wolfman brought a sense of narrative cohesion. His writing wasn’t flashy, but it was solid—structured in a way that suggested someone who understood the FF and knew how to keep the engine running, even if he wasn’t driving it into new territory.

Keith Pollard, meanwhile, turned in some of the cleanest, most professional superhero art of the Bronze Age. His designs were sharp, his action scenes clear, and his storytelling was always easy to follow. He gave the book a visual consistency it had been missing since Pérez’s departure, and there’s something to be said for how reliable that made the comic feel month-to-month.

Story-wise, there were some solid beats: Doom remained a constant, if not especially reinvented, threat; Ben’s insecurities bubbled under the surface; and Sue and Reed’s relationship was explored with a bit more emotional maturity than earlier eras. The threats ranged from alien invasions to high-concept science fiction dilemmas, and while none of them reached Lee/Kirby-level stakes, they still carried weight.

Wolfman wasn’t trying to revolutionize the FF. He was trying to stabilize them. And he succeeded. In fact, his run is probably more important than it gets credit for—it laid enough groundwork and momentum for the Byrne era to finally come in and reshape the title in a major way. Without that foundation, Byrne’s reinvention might not have landed quite so effectively.

It’s a run that rarely tops anyone’s “must read” list, but when you revisit it, you’ll find a creative team doing honest, heartfelt work to keep Marvel’s First Family feeling like a family.

John Byrne

There’s a reason so many cite this as the definitive FF run post-Kirby. It’s mature without being cynical, dramatic without being overwrought, and adventurous without losing its emotional anchor.

If all the post-Lee/Kirby runs were stepping stones, then Byrne’s run was a full-blown country. Not a soft reboot, not a side detour—an outright renaissance.

For the first time, Sue Storm truly stepped into her power—not just as a team member, but as a central force in the narrative. She became the Invisible Woman, not just in name but in presence. Byrne gave her agency, leadership, and emotional depth that had rarely been explored before. Reed was still the cold, brilliant scientist, but now with a sharper edge and greater flaws. Johnny felt more grounded, more believable. And Ben? Ben was heartbreak on two legs—a lovable pile of orange rock with layers of vulnerability.

The stories themselves are absolute bangers. Doom is dethroned in a long-simmering arc that explores both his pride and his vulnerability. Galactus returns, tattered and weakened, but still godlike. Franklin Richards’ powers become a terrifying wildcard. There’s a terrifying trip to the Negative Zone that leaves Reed facing impossible decisions. And yet somehow Byrne keeps the book lean. It’s tightly paced, always moving forward, never indulgent.

Byrne’s dual role as writer and artist meant the visual and narrative tones were perfectly aligned. His clean lines and sharp layouts made even the most cosmic nonsense feel digestible. He had a keen eye for scale, allowing quiet family moments to sit side-by-side with sprawling interdimensional chaos.

There’s a reason so many cite this as the definitive FF run post-Kirby. It’s mature without being cynical, dramatic without being overwrought, and adventurous without losing its emotional anchor. And yes, Vanessa Kirby citing this run as essential prep for her Invisible Woman role? Absolutely the right call.

This run didn’t just respect the past—it built a future. It showed the world how to make the Fantastic Four fantastic again.

Roger Stern & John Buscema

Sometimes, solid craftsmanship is enough.

Roger Stern’s short stint on Fantastic Four doesn’t get talked about much, but it left a solid impression on me. After the high bar set by Byrne, and with the title still recalibrating, Stern offered something that felt like a respectful cooldown. It didn’t try to top what came before—it just tried to work, and for the most part, it did.

The stories had a back-to-basics charm, even if they didn’t push boundaries. Stern leaned into the family dynamic again, with plots that were a little more subdued but still carried that essential FF flavor—exploration, conflict, a bit of weird science, and a dose of heart. John Buscema’s art, meanwhile, brought a classic Marvel sensibility to the title. It wasn’t experimental or edgy, but it was confident and grounded. There’s something nice about a book that knows what it is.

Stern and Buscema’s run won’t top any “Best of FF” lists, but there’s no shame in being a dependable chapter in the team’s history. Sometimes, solid craftsmanship is enough. This was a brief but worthy breather before the title would once again try to shake things up.

Steve Englehart & Keith Pollard

Another stepping stone—though this one tried to shake the table. Unfortunately, editorial interference made that difficult. Englehart introduced a dynamic that would recur more often than you’d think: the idea of team members temporarily stepping away from the FF. I like the idea of tweaking the status quo, and this was definitely memorable for doing that. Pollard’s art stayed strong, with a classic superhero feel, but it couldn’t push the title into greatness on its own.

Walt Simonson

Simonson’s goal was to remind readers that this book could be a blast—a cosmic, time-twisting, big-brain science romp with heart.

Walt Simonson’s run on Fantastic Four felt like a shot of adrenaline after a long stretch of narrative maintenance. It wasn’t as emotionally deep as Byrne or as grandiose as Hickman, but it didn’t need to be. Simonson’s goal was to remind readers that this book could be a blast—a cosmic, time-twisting, big-brain science romp with heart.

As both writer and artist, Simonson brought a singular vision to the book, and that cohesion paid off. The art was bold and dynamic, full of crackling energy and wild tech. His storytelling felt larger-than-life, leaning into concepts like time loops, alternate realities, and bizarre temporal physics. He took the team to the edge of space and time—sometimes literally—and made it feel breezy and exciting. There was a confidence in his weirdness that carried everything forward.

It wasn’t a perfect run. Some emotional beats got a little lost in the spectacle, and not every issue hit as hard as it could have—but the vibe was right. This run didn’t need to rewire the FF’s DNA. It just needed to say, “Hey, remember how cool this book can be?” And it did. Loudly. With a Kirby-sized hammer.

Tom DeFalco & Paul Ryan

This wasn’t the coolest Fantastic Four run. But it might be one of the most committed.

Tom DeFalco’s run with Paul Ryan is often dismissed as too melodramatic, too ’90s, too soap opera—and all of that is kind of true. But here’s the thing: it worked. For all its excesses, this era of Fantastic Four had a pulse. It had drama. It had heart.

Sure, the infamous Sue Storm “boob window” costume is easy to mock—and rightly so—but there was actually a story reason behind it. And more importantly, beneath that questionable wardrobe choice was a run genuinely invested in the emotional lives of its characters. Johnny’s romance with Lyja added layers of mistrust and longing. Ben and Alicia’s rekindled relationship carried emotional weight. Even Ben’s temporary romance with She-Thing (Sharon Ventura) gave the run a sense of lived-in, messy authenticity.

DeFalco wasn’t afraid to shake up the status quo. Psi-Lord. Franklin growing up (sort of). A deeper exploration of Reed and Sue’s parenting struggles. This run leaned hard into continuity and legacy in ways that sometimes felt convoluted, but always felt earnest. And as someone who first read parts of this era as a kid? It hit even harder on the reread. Nostalgia aside, there’s a raw sincerity here that’s easy to appreciate.

Paul Ryan’s art might not have been flashy, but it was consistent, clean, and built for the kind of dramatic, continuity-heavy storytelling DeFalco was aiming for. He kept the emotional beats readable, the action clear, and the tone steady—exactly what this kind of soap-operatic run needed.

This wasn’t the coolest Fantastic Four run. But it might be one of the most committed. And in a team built on love, loss, and loyalty, that commitment matters.

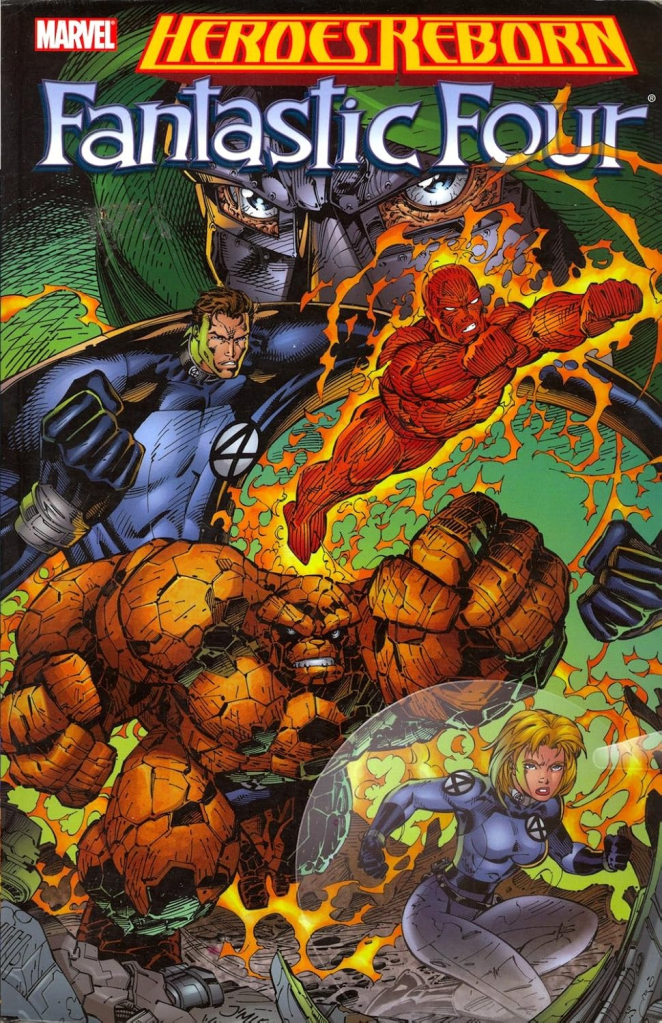

Heroes Reborn / Return

I’ll admit it… I skipped most of Heroes Reborn. I just didn’t like it. I read the first and last issue. As a person who generally liked reimaginings of characters (see: both Ultimate Universes, Spider-Man 2099, Spider-Girl, the Absolute line of current DC, etc.), seeing the FF turn into what I would ostensibly call Image Marvel just felt weird and out of left field. And I like Jim Lee’s art! I’m just uninterested in that whole ’90s “let’s be edgy for edge’s sake” vibe that was going on.

I also only read a little bit of Heroes Return. If I didn’t like what came before, I obviously wasn’t particularly interested in its end.

Fantastic Four: 1234 by Grant Morrison & Jae Lee

Morrison’s intent was clear: deconstruct the FF.

Grant Morrison’s Fantastic Four: 1234 was one of the most frustrating parts of this journey. Morrison is a writer I usually love—brilliant, bold, and unafraid to tear superheroes down to their essence and rebuild them into something stranger, sharper, smarter. But here? The scalpel went too deep.

Morrison’s intent was clear: deconstruct the FF. Examine them as mythic archetypes. Strip away the comfort and familiarity to show us the weird, fragile things underneath. But in doing so, the team stopped feeling like the Fantastic Four. Reed becomes emotionally alien. Sue is an icy cipher. Ben and Johnny are reduced to vague thematic sketches of themselves. They don’t feel like a family—they feel like symbolic projections of one. The heart gets lost in the concept.

And yet… Jae Lee’s art is stunning. Truly. His moody, Gothic atmosphere and haunting character designs give the book a dreamlike tone that almost convinces you it’s deeper than it is. Every page looks like it belongs in a gallery. The art wants you to feel something powerful. And sometimes, it succeeds—especially in scenes of isolation or quiet dread.

But ultimately, this is a book that admires the idea of the Fantastic Four more than the reality of them. It’s a thought experiment. A slow-motion explosion. Beautifully rendered, but emotionally distant. An interesting detour on the road, but not a place you want to live.

Mark Waid & Mike Wieringo

This run is one of the most accessible, heartfelt, and high-stakes chapters in FF history.

Mark Waid’s run felt like a true celebration of everything Fantastic Four is meant to be: fun, bold, emotional, and deeply rooted in both science fiction and familial love. It took the best elements from the past—Byrne’s character growth, Kirby’s cosmic imagination—and modernized them into something that felt vital again.

Right out the gate, Waid makes a powerful statement: Reed Richards isn’t just a brilliant scientist—he’s an explainer. A man who believes that understanding is the key to solving any problem, no matter how cosmic or personal. That theme echoes throughout the run, grounding the wild sci-fi madness in something fundamentally human.

The arc with Doom is an all-timer. Not content with just being the arrogant dictator in a metal mask, Doom dives headfirst into sorcery—flaying a woman alive to craft a suit made of skin. And no, that’s not just edge for edge’s sake. It’s deeply unsettling and reframes Doom as a villain who will sacrifice literally anything to achieve power. He’s no longer Reed’s twisted mirror—he’s Reed’s opposite, rejecting science in favor of primal dominance. It’s horrifying. It’s mythic. And it works.

Waid also finally gives Reed and Sue’s marriage the respect it deserves. Their relationship is full of tension, tenderness, and growth. Johnny is actually funny again, and Ben is—of course—the heart of the team, but also given more self-awareness and pathos than usual. Every member of the team gets the spotlight, and it never feels like Waid is picking favorites.

Wieringo’s art never quite landed for me. It’s not that it was bad, but it felt like a mismatch for the material. His cartoonish, rounded style lacked the texture and dramatic weight the stories sometimes called for. There’s a difference between playful and flat, and for me, Wieringo’s work teetered toward the latter more often than not.

That said, it was serviceable. The characters were expressive, the layouts were clean, and the pacing was solid. When the story needed to hit an emotional beat or deliver an action moment, it got the job done. But it rarely elevated the material. It felt like it was along for the ride rather than helping drive it. In a run that hit so many emotional highs, the art was often the weakest link—never sinking it, but never quite soaring either.

This run is one of the most accessible, heartfelt, and high-stakes chapters in FF history. It’s big without being bloated, emotional without being maudlin, and smart without ever talking down to you. If someone asked me, “Where should I start with the Fantastic Four?”—this is where I’d point.

Marvel Knights: Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa & Steve McNiven

This era wasn’t about the biggest cosmic threat or the flashiest redesign. It was about fear, family, and failure.

This run flies under the radar for a lot of readers, but it absolutely deserves more attention. Aguirre-Sacasa approached the Fantastic Four like a playwright—deeply invested in the emotional and philosophical weight of each character. The stories weren’t splashy, but they were human, and at times, painful in their clarity.

One issue in particular left a mark on me: a deeply affecting moment between Reed and a suicidal man. It’s written with such tenderness and honesty that it brought me to tears—something no other FF issue has ever done. That quiet sincerity, the way it handled mental health without preachiness, felt rare in superhero comics, especially then.

This era wasn’t about the biggest cosmic threat or the flashiest redesign. It was about fear, family, and failure. About the weight of Reed’s intellect, the fragility of relationships, and the unglamorous day-to-day moments between missions. Aguirre-Sacasa brought a literary depth to the book that few others have even attempted.

Steve McNiven, still early in his career, brought detailed, grounded art that perfectly suited the tone. It wasn’t stylized or cosmic—it was intimate, expressive, and anchored in realism. That helped the emotional beats land even harder.

This wasn’t a redefining era. It was a quiet triumph. And like the best Fantastic Four stories, it reminded us that beneath the powers and the portals and the pomp—this is a story about people who love each other, and the ways they fail and forgive.

J. Michael Straczynski & Mike McKone

Straczynski’s run on Fantastic Four is one of the more curious stretches in their publishing history. Coming off the back of Waid’s high-energy reinvention and before the cosmic reshaping of Hickman’s era, JMS offered something quieter and more introspective—but also occasionally meandering.

His biggest contribution was digging deep into Reed and Sue’s marriage. Following the fallout of Civil War, where Reed supported the Superhuman Registration Act, their relationship was on the brink of collapse. Straczynski wisely leaned into that fracture rather than papering over it. Reed’s internal guilt and obsessive need to “solve everything” were finally addressed with emotional weight, and Sue’s quiet strength carried much of the heart. While it didn’t land every beat, it set the emotional groundwork for later stories—especially Hickman’s cosmic epic.

Outside of that, though, the run often felt like it was circling something larger and never quite landing it. There were moments of philosophical depth, particularly with Reed wrestling with his place in the world as a scientist, father, and husband. But plot-wise, it never reached the heights it aimed for. It was thoughtful, but not quite thrilling.

Mike McKone’s grounded art matched this more introspective tone. It wasn’t explosive or flashy, but it didn’t need to be. It captured character emotion effectively, and the book always looked clean and readable.

Ultimately, this run is remembered less for its plot than for its tone. It was a transitional period—subdued, emotionally cautious, and a bit uncertain about where the team should go next. Not essential, but certainly not without value.

Dwayne McDuffie

The Dwayne McDuffie run caught a lot of flack back when I was frequenting message boards. I remember being frustrated by depictions of Doctor Doom being racist at the time, and the “woke-before-woke-was-a-word” decision to include Black Panther and Storm on the team rubbed me the wrong way back then. It’s interesting what time does to the mind. Those things that irked me in my early twenties just don’t now. Maybe it’s exhaustion with the whole discourse, or maybe I’ve just grown up.

This run wasn’t long, but it was packed. McDuffie clearly respected these characters and was eager to try something new without tearing the house down. The team dynamics worked. The dialogue popped. The FF felt like they were adapting to a new status quo without losing their identity.

Yes, the Silver Surfer armbar by Black Panther was absurd. Everyone talked about it like it broke the internet before that was even a thing. But it didn’t undermine the fact that this run had actual stakes and heart.

The art did its job without distraction. It wasn’t flashy, but it didn’t need to be. It told the story cleanly and confidently—exactly the right fit for what McDuffie was building.

Mark Millar & Bryan Hitch

Mark Millar’s run surprised me by being better than I expected. I went in nervous—Millar is a guy whose work I often enjoy, but he’s also a deconstructionist through and through. And when you’re coming off of Ultimate Fantastic Four, where he literally tore them down to rebuild them into something else, it’s hard not to wonder if he’d do the same again in the mainline.

But this time, he didn’t. This wasn’t another teardown. It was more grounded, more respectful of what came before—even if it lacked some of the emotional warmth or family dynamic that defines the team at their best. It was serious, occasionally grim, and maybe a little too self-important at times, but it never broke the foundation.

What really helped was Bryan Hitch on art. The man draws epics. There’s weight to every panel. Even when the scripts felt slightly off-tone for the FF, Hitch gave it scale and purpose. His widescreen, cinematic style made the book feel important, even if the stories didn’t always land with full impact.

Overall? Not essential, but not forgettable either. A serious, glossy entry that didn’t betray the FF’s spirit—and considering the era it came out in, that’s more than enough.

Jonathan Hickman

This wasn’t just a great Fantastic Four story. It was one of the greatest Marvel stories.

This is, without a doubt, my favorite run of Fantastic Four. It might even eclipse Byrne for me—and that’s saying something. Hickman didn’t just write the Fantastic Four; he orchestrated them. He approached the title like a symphony, layering motifs, weaving callbacks, and conducting big ideas with precision. And like any great symphony, it didn’t just sound impressive—it felt profound.

From the moment the Council of Reeds appeared, you knew you weren’t reading a typical superhero book. Hickman was playing with philosophy, legacy, and multiversal existentialism like it was Tuesday. Reed’s obsession with solving everything became the emotional anchor of the series—a blessing and a curse that shaped the lives of his family and the fate of entire realities.

The Future Foundation gave the title new life. Valeria Richards whispering dangerous ideas to Doctor Doom. Doom cooperating with the FF because the stakes were that high. A dead Johnny Storm sacrificing himself in the Negative Zone. Spider-Man seamlessly joining the family. Franklin Richards bending reality while growing into his powers. Every beat had weight, and every issue felt like a puzzle piece locking into a larger vision.

But Hickman didn’t just throw in lore and walk away—he earned every twist. The pacing could be glacial at times, but that only made the payoffs land harder. When Johnny returned? I cheered. When Reed confronted the cost of his intellect? I hurt. When Doom said “I love you, Valeria,” I felt like I was reading comics with the training wheels off.

The rotating artists—Epting, Dragotta, Stegman, and more—rose to the challenge. Whether the story called for sterile science labs, high-energy action, or heartbreaking intimacy, the art team never dropped the ball. Their work matched Hickman’s scripts in tone, ambition, and elegance. It looked like high-concept Marvel. Because it was.

Yes, sometimes the emotional intimacy was traded for cosmic scale. But that wasn’t neglect—it was thematic. Reed was losing sight of his family because he was trying to save the multiverse. Hickman wasn’t forgetting the human core—he was showing us what happens when it’s stretched too far.

This run is what happens when you give a writer with vision the room to build. It didn’t just elevate the FF—it rewired the Marvel Universe around them. When it ended, I didn’t want more issues. I wanted to start over and read it all again.

This wasn’t just a great Fantastic Four story. It was one of the greatest Marvel stories.

Matt Fraction & Mark Bagley (and Mike Allred)

I wanted to like this more than I did. The premise was intriguing—Reed and the gang set off on a family road trip through time and space while another team (the replacement FF: Ant-Man, She-Hulk, Medusa, and Ms. Thing) stayed behind to handle day-to-day disasters. Conceptually, that’s gold. In execution, though, it just didn’t do it for me.

The stories never quite clicked emotionally, and something about the detachment from the wider Marvel Universe made it feel… adrift. It also didn’t help that this came at a time when Marvel’s publishing choices made you wonder if they were trying to downplay the FF’s importance altogether.

That said, Mike Allred’s art on FF was a visual treat. His off-kilter style worked well for that book’s tone and gave the oddball team a distinct flavor. Bagley, ever the solid pro, kept Fantastic Four grounded with his clean storytelling and reliable expressions. Both were doing good work—even if the scripts didn’t always rise to meet them.

James Robinson & Leonard Kirk

It was almost tragic the way Marvel treated the team during this era. This run felt like the schoolyard bully insisting on playing with your favorite toy and then slowly breaking it in front of you—and narrating every crack. Thanks Marvel, you’re an asshole.

I actually really like James Robinson. He’s a great writer when given the room to build something lasting, but this felt like he was handed a mandate: “Write the end. Make it sad.” And he did.

The FF were dismantled legally, physically, emotionally. The team was put through the wringer and then some. Reed and Sue’s marriage, Johnny’s confidence, Ben’s sense of purpose—all strained to their limit.

Leonard Kirk’s art was solid throughout. It captured the sense of erosion happening to the team, matching the tone beat-for-beat. He didn’t go over the top, but you could feel the sadness in the panels.

This wasn’t a triumphant return—it was a funeral march.

Secret Wars (2015)

Thank GOD Hickman was the one to close the curtain on this era of the Fantastic Four. It was less a series finale and more a cosmic opera—loud, tragic, and astonishingly earned. Everything he had built from his Fantastic Four run and Avengers/New Avengers culminated here. And it wasn’t just an ending for the FF—it was the end of the Marvel Universe as we knew it.

The multiverse was collapsing. Incursions had ravaged reality. And at the center of it all, Victor Von Doom sat on the throne of Battleworld as a literal god. God Emperor Doom wasn’t just the most powerful villain in the Marvel Universe—he was its twisted savior, stitching worlds together from the ashes. Reed Richards, meanwhile, was the only man who could challenge him—not with brute strength, but with intellect, integrity, and purpose.

I’ll admit: coming into this without the full context of Hickman’s Avengers run was like walking into the last act of a play and trying to piece together the script—but even so, the emotional weight still landed. Doom ruling with Sue and the kids by his side? Heartbreaking. The final confrontation where Molecule Man tips the scale? Riveting. Reed reclaiming his role not just as a scientist or a father, but as a creator—the man who solves everything—was transcendent.

And when it was all over, it was Reed, Sue, and their children—not the Avengers, not the X-Men—who were entrusted with rebuilding the multiverse. That’s the legacy Hickman left the FF with: the foundation of everything.

Esad Ribić’s art elevated it all. Every page felt like a fresco pulled from a god’s fever dream. The lighting, the scale, the compositions—it was museum-worthy. Hickman wrote mythology; Ribić painted it.

Secret Wars wasn’t just an event—it was a love letter, a funeral dirge, and a resurrection all in one.

The Fantastic Four-less World

Marvel scaled back both the FF and the X-Men during this time. The rights disputes were never officially confirmed as the reason, but c’mon—we all knew. It was glaring. The book was absent. The characters were dispersed. There was no Fantastic Four.

And knowing the history behind it—the politics, the pettiness—it just made the whole thing more bitter than sweet. I wasn’t hopeful. I was annoyed. The entire time, I found myself flipping through issues just clamoring to get to the moment they finally return. I didn’t care about Ben Grimm joining the Guardians of the Galaxy. I didn’t want Johnny Storm dating Medusa. I wanted the family back. Anything less felt like crumbs.

It wasn’t just about seeing these great characters. It was about the heart of the Marvel Universe being forcibly hollowed out.

Fate of the Four (Marvel Two-in-One)

This is where I’m currently at in my readthrough. Chip Zdarsky’s take isn’t bad—actually, it’s quite good. The writing is emotionally grounded, with Johnny and Ben processing grief in very believable ways. Doom’s involvement is compelling too, bringing a strange, reluctant dynamic to the team’s temporary form.

Visually, the book looks great. Jim Cheung and Valerio Schiti bring strong linework and dynamic layouts that elevate the quieter, more introspective moments as much as the big action sequences. The paneling feels confident and clear, and the characters emote beautifully—even when they’re hurting.

But like the era that preceded it, it’s frustrating. We’re still not seeing the team back together. Johnny feels like a depressed golem of his former self, and it’s exhausting. I want to see him happy again. I want the spark, the joy, the weird science, the cosmic energy that comes from having all four together.

To be honest, I hit a bit of a wall. Real life got in the way, and I paused my reading somewhere in the middle. But I’m hoping writing this article reignites my motivation. I will finish this journey. With any luck, I’ll be fully caught up before Fantastic Four: First Steps hits theaters.

Conclusion

That was a lot. Attempting to read the First Family from beginning to end—even skipping a few hundred Lee and Kirby issues I’ve read before—is no small feat. It’s overwhelming. It’s inspiring. It’s downright exhausting. But more than anything? It’s worth it. There’s a reason these four have stood the test of time, even as Marvel’s spotlight shifted elsewhere.

What’s entirely hilarious (and maybe a little predictable) is that even after all this, I’m already thinking: who’s next? Which corner of the Marvel Universe do I dive into now? … Or maybe DC? Maybe I’m just a glutton for long boxes and confusing timelines.

What was your favorite Fantastic Four run? Was it one of the big ones—Lee/Kirby, Byrne, Hickman—or one of the underrated gems like McDuffie or Robinson? Or maybe you’re someone who actually liked 1234 (and I promise I won’t judge too hard).

Also—what run should I tackle next? Should I dive into Thor? Go cosmic with Silver Surfer? Revisit the Avengers in full?

And finally: are you excited for the new Fantastic Four: First Steps movie? Do you think it can recapture the magic?

Leave a reply to It’s Clobberin’ Time!!! A Review of Fantastic Four: First Steps – Ginothy Tonic Cancel reply